There are more and more events every year dedicated to video games. Navigating through the annual schedule is getting increasingly complex, and we have many discussions with our different partners about the merits of the different events for them to attend, depending on the profile of their games, the current state of development of the projects, and the company’s long term goals.

I spend a fair amount of time at these events for our own reasons, and I have been toying with the idea of a guide for anyone feeling a bit lost on the topic. This blog post is the first attempt at such a guide. The idea is not to tell you which events to attend, mostly because there is not one size fits all answer to this question, but to breakdown what roles these events play in the life of a game, and of a studio.

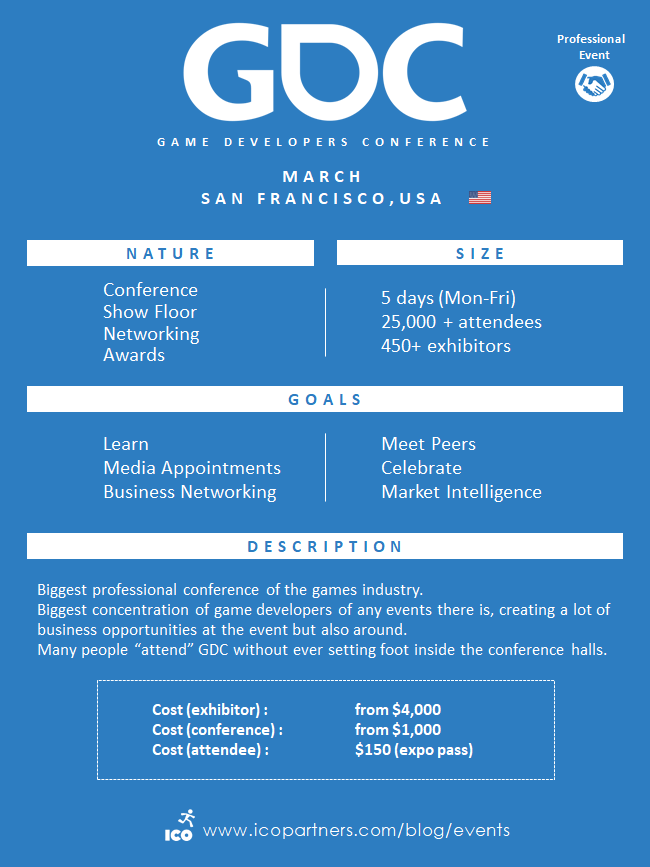

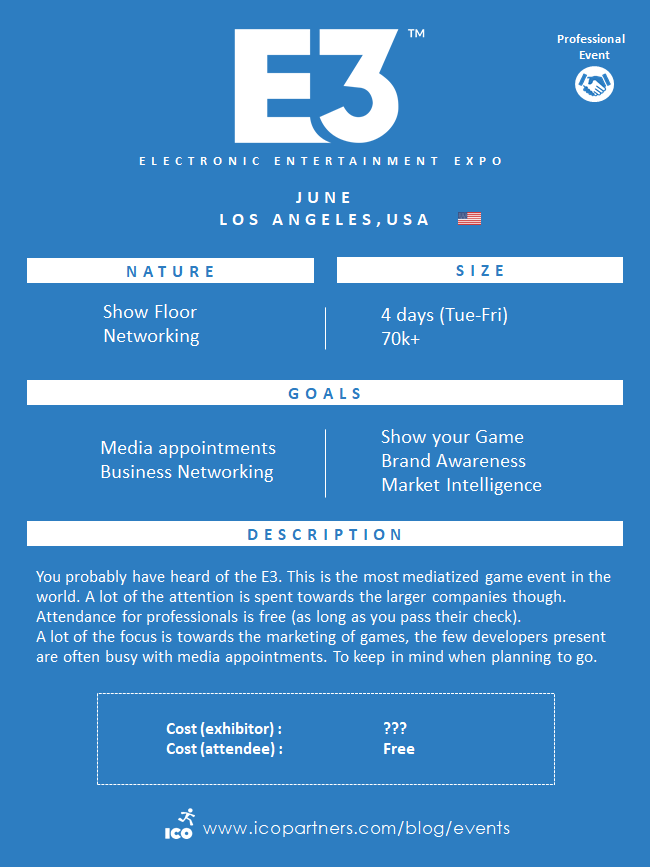

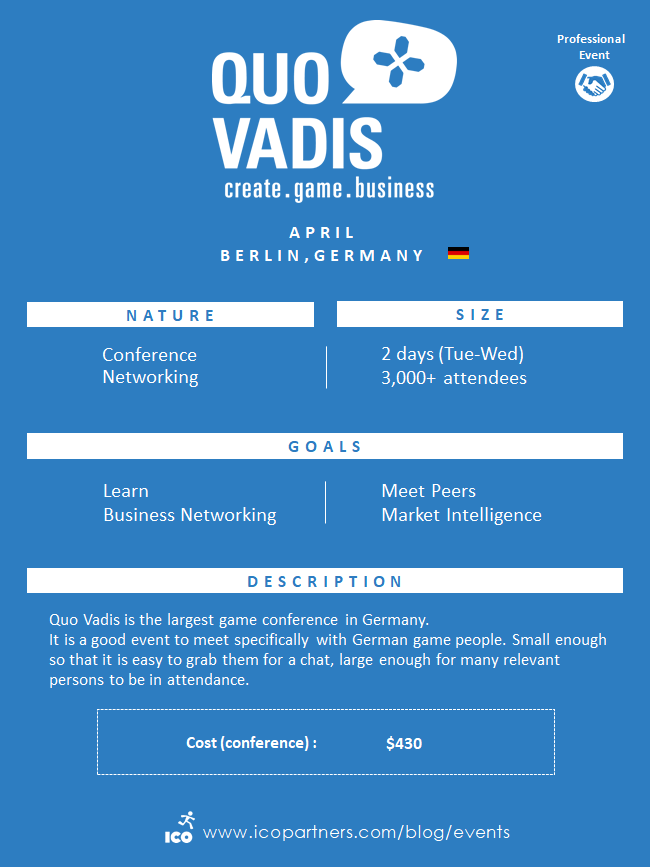

The other important component is the idea of an event id card (I sometimes call them events stats blocks, because of reasons) – a single-image summary of what an event is about (a two- or three- images summary for those events that have fundamentally different components to them), and what it is good for, hopefully helping you decide which are the ones you should definitely attend.

The blog post is very much structured as a guide to understand these event id cards, explaining the different parts and helping you decide what matters the most to you, your project and business when attending an event, along with a first batch of cards for the main industry events.

Events ID cards explained

The event id cards are broken into the following components:

- Name of the event.

- Usual time of the year it happens (the month).

- Location (city, country).

- Type of audience. Whether this is a professional event (B2B – Business to Business), or a public event (B2C – Business to Consumer). Events with both components will get an id card for each of them. More details below.

- Nature of the event. What the event is. I will go in more details about each category you can find here. I will also go into detail on each possible option later on.

- Event Size. General information about the duration of the event and its size.

- Goals. What is the usual motivation to attend the event. I will also go into detail on each factor.

- Description. Don’t expect any lengthy text here. It is mostly to provide context.

- Cost to attend. These are bare minimum costs and don’t go take into consideration travel and lodging. I think this is important to have, but take this with a massive grain of salt and DO NOT use it for budgeting purposes. Always build your budget using actual pricing information from the organizers.

Types of audience

The most basic categorisation of events is based on what type of audience it is intended for. This quite simple, as there are two possibilities:

- Public events are intended to be for anyone who cares to attend. They are not necessarily free, but there is an understanding that anyone can go there and the content is aimed at the general public. These are also referred to as B2C events (Business to Consumers) and they can be conventions, exhibitions, or even conferences. Most often these have a showfloor where you can exhibit your game to the general public.

- Professional events are intended for professionals (or would-be professionals) of the game industry. They are also referred to as B2B (Business to Business events), and there is a huge variety of them.

Of course, some events have both public and professional components – gamescom for instance has an area dedicated to professionals and closed to the public, while most of the space is taken up by booths showcasing games for the public.

In those cases, I will make an event id card for each side of the event.

Nature of the events

This is what will tell you what actually happens at the event. Many events have different types of activities and related content, so expect to see multiple categories to match a single event.

- Conference. You have speakers, and maybe round tables, sometimes you sit down in the audience and listen, and other times you contribute to the discussions.

But mostly, you have someone telling you things, you listen to them, and you learn something. - Show Floor. You have a space, more or less a large one, where exhibitors have set up booths to present their products. Show floors for Public Events will more likely be about showcasing games that are not out yet, and for the public to discover them ahead of their friends. Show Floors for Professional events can be a mix of showcasing games, presenting new technologies, trying to sell developers the latest ad-technology to maximize users acquisition. Here you will also sometimes find recruitment booths. Certain events have huge dedicated spaces for recruiting activities.

- Networking. The event is set up so that it is easy for meetings to take place. There might be meeting tables, meeting points, and the event may offer a matchmaking service to make it easier for you to find the type of person you want to meet.

- Awards. The event includes an award ceremony. Some are more sophisticated than others. These range from taking over a conference room when the time comes to announce the winners, to a full-on dinner party with a host and entertainment around the awards announcements themselves.

- Competition. These are esports events – competitions organised around a number of video games. Generally, they will be Public Events.

Most of the events I will cover are mainly of the first three types – the vast majority of events relevant to professionals of the game industry would have at least on those component at the heart of what they offer.

Goals

Why do you attend events?

What is it you want to achieve by attending?

These might seem obvious questions, but there are many studios and developers that are attending events, spending significant amounts of money and time, just because they feel that’s what is expected of them, and attending this event or another is what they should do, without going through the process of mapping out what they want out of attending them.

Here are the most common discussed motivations to attend events when working with games studios and publishers:

- Learn

- Media Appointments

- Business Networking

- Meet your Peers

- Show your Game to the public

- Meet your Community

- Sell

- Celebrate

- Building Brand Awareness

- Market Intelligence

Learn

Most commonly seen at conferences, where sharing knowledge is a formalised component of the event, learning can also be expected at any event where you have the opportunity to speak with your peers about specific aspects of your projects, and learn from others’ projects. This is a very straightforward reason for attending, albeit one not easy to evaluate the ROI on.

You might expect a specific event to be rife with sharing of like-minded individuals, but there is usually no formal process to make that happen; you might attend a conference where the key topics for discussion are on matters that you, or your studio, have already mastered.

It is important to consider the importance of what you want to get from an event in that regard, to double check the speakers’ backgrounds and their previous speaking engagements. To that effect, you can search for their names on YouTube, or you can have a read through their Twitter timeline, to build a better picture in regards to what to expect.

Events that rely heavily on conferences and content are very careful about their reputation, and usually spend a significant amount of energy securing good speakers and curating their program. Checking for an event’s reputation ahead of time, asking previous attendees about their experiences there, is another good idea, and particularly important if your main objective is learning.

You should also consider whether the event is recording its content and distributing it afterwards (some will will have their content behind a paywall while others will share it for free). You might not get the extra warm feeling that you have when you breathe in the same air of a respected expert of your field, but you will likely save a lot of money.

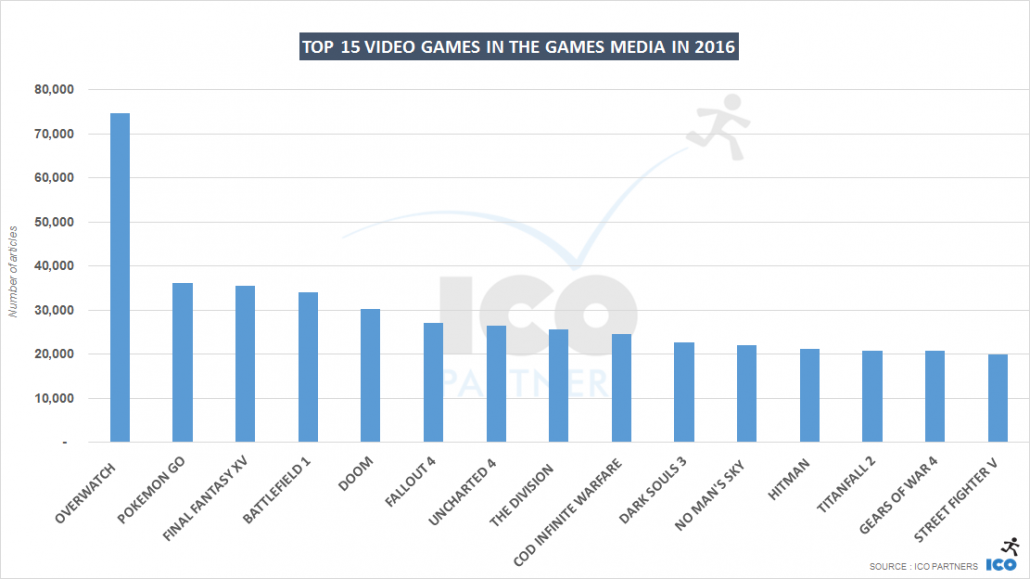

Media appointments

You have a great game, and you want to put it in the hands of journalists, getting them excited about it and, hopefully, to write about it.

For certain events, the media attendance can be one of the main motivation for studios to go. This is certainly true for gamescom in Europe, for instance, where the calendar of the event has even a dedicated day for press (even though at gamescom media appointments will happen throughout the event, as well as in the halls dedicated to the public side).

The trick is here is not to expect that showing up is all you have to do. At any event, if your goal is to present your game to the press, you need to work ahead of the event to invite them to drop by your booth. Many events will provide you with a list of the attending media, as long as you are yourself a paying attendee, most often with a booth. But these media lists can be deceptive. They will include everyone who has registered to get a press accreditation and received it. It means multiple things:

- Some will be very small. Possibly so small that it can be difficult to appreciate how much of your time is worth investing with them.

- Some will be attending with a specific agenda in mind. Whether or not you fit that agenda can be hard to appreciate ahead of time.

- Some outlets won’t have many people on site. If you know a major website is attending, don’t rejoice until you know how many journalists are coming. If they send a single person to a large event, they will likely prioritize larger games, and getting their attention will be hard.

- Some will have registered “just in case”. They are on the list, but they might not be coming at all. They just ensured they had a badge ahead of time, before even deciding if they’d attend.

- Some will not attend the whole event. They might be in there for a day, an afternoon, or even just a couple of hours. Do not assume that everyone is on site for the full event’s worth of time. It is also common for media to skip the weekend days, most often the B2C period, to stick to week days, and many journalists will go home on Friday evening.

You will have some foot traffic, the odd media person whose meeting was canceled and they’re wandering around, trying to find a hidden gem in the giant haystack that conventions can be, but it will more likely be a smaller media representative who was not significant enough to secure appointments with bigger projects, and has more time on their hands than their larger counterparts. And if you have free time of your own, small streams can make big rivers, but keep an eye on the objective and your priorities at all time.

Another point to keep in mind in regards to taking media appointments, be aware of the media that are important to your specific niche. The big generalist outlets are great, but so are niche websites that represent a perfect fit with your project. The return you can get from those highly specialised journalists can prove more beneficial than a small paragraph produced quickly for a larger publication.

Lastly, make sure you double check an event’s media presence. You might assume that some festivals are bursting with journalists left and right, only to realize they are rather poorly attended by media and you made your assumption because your own media bubble has a particular affinity with those events. Time is at a premium for video games editors and journalists, and they only attend events they know will provide them opportunities for content that makes up for the time spent away from their desks.

Business Networking

Whether you want to present a game to a publisher, you want to find some contract work to help your cashflow, or you want to meet with a service provider, your goal is business oriented and you want to spend time to discuss your project with potential partners.

Some events are designed to facilitate these types of discussions. Ahead of the first day, they will invite you to list your company and your project on a matchmaking system, and you will have the ability to consult all the attending companies and their projects, and contact them through said matchmaking system. This is where a couple important disclaimers need to be made:

- Not all matchmaking solutions are of equal quality. The worst one I had to use was probably at Gstar, the biggest game event in Korea, in November every year in Busan. Gstar is great, but their matchmaking is horrendous! Or it was last time I attended, a couple of years ago, but I haven’t heard anything hinting at it having improved. Be prepared to suffer, though, as they still provide very valuable information on who is attending.

- Not all matchmaking solutions are actually used. And this can be related to the point above – bad systems are avoided by most attendees – but it can also be because of the profile of the event and habits that attendees have built prior to a matchmaking system being added. Don’t necessarily assume that everyone is using the matchmaking, and always pursue other channels to get in touch with the person you want to meet.

In the absence of a matchmaking solution, you have other ways to find out who is attending an event. At conferences, the list of speakers is the first resource to leverage. They will be busy when they are having their own talks, but most of them are likely attending to network as well. Then, you can check the exhibitors lists, and the sponsors list. These companies are spending money to let the world know they are attending – they will likely be open to meet you. Then, many people in the industry announce their attendance to events through social media – a quick search for the name of the event on Twitter can give you ideas on who to reach out to for your meetings.

Of course, you can also just reach out to people you would like to meet and ask them whether they are attending or not. Even if they are not, that’s an opportunity to find out which events they are headed to, or to arrange a follow up to present your project through a Skype call, or equivalent, when they are not too busy.

When your goal is to organise business meetings, it is likely you have a very specific idea of what you want to get out of your attendance, and whether the event was fruitful should be easy to determine. How many publishers have you met? How many of them showed interest and asked for a follow up after the show? Have you identified potential partners looking for help and who are interested in contracting you? Just keep in mind that while events are great to network and create business leads, the hard work happens after those meetings (and sometimes before, as you have to make sure you show the best you can do during at those discussions), and any positive business discussion you had will take time to bear fruits, and many of them won’t.

I also find it is important to keep an eye on the long-term benefits of those encounters. While you might be disappointed that the publisher you wanted to work with told you they have a full portfolio and they are not looking for more new games at the moment, that encounter can be beneficial further down the road as they now know you, and they will be more likely to meet you again in the future for other projects. You will also have a better understanding of what they like, and how to pitch to them.

Meeting Your Peers

Making a game can be a very exhausting process. Many studios end up working on their game for several years, with the same team of people involved every day. And even if you can share your thoughts and listen to others going through the same process online, there are proven benefits in going out into the world, taking a break from development, and meet with likeminded people at an event.

For some, this is a way to get inspired by their peers’ stories; others are driven by the positive feedback they can get by sharing the details of their project; or they can be recharging their batteries by making sure that they are not alone and that there is a whole industry, comprised of many peers, helping them and validating what they are doing.

This is obviously a motivation where the ROI is much harder to define, and very personal. I have met developers who hate attending events as it takes them away from “the real work”, while others say they regularly need to connect with other game makers.

Certain events are more suitable than others for this. First, you should consider what are the other motivations that will attract other industry folks there. It is harder to connect and casually discuss at a large B2C event where everyone also has to man a booth, while it would be much easier at a conference, where the schedules are more flexible, and often have breaks to allow attendees to connect. Then, you need to consider the type of person that you are likely to get along with, and whether they are likely to attend the event in significant numbers. An indie developer is likely to have a hard time finding like-minded individuals at a free-to-play mobile event, for example.

Twitter is again a good source to determine whether or not an event would be suitable for you. You are likely following said like-minded persons, and whether or not some of them are going to attend (or would consider attending, as you can ask them), is an excellent indicator.

Ultra-niche events tend to be good for this purpose. Attending AdventureX in London if you are making a point-and-click adventure game is probably a good idea if you want to meet your peers. And of course, meeting game people will also help you fulfil other motivations (business networking; learning), but I think purely meeting your peers is a valid and often not mentioned motivation.

Show Your Game to the Public

You have been working on your game for a number of months, and even though it is not done, you are itching to show it to the world, and to put controllers into the hands of strangers, seeing the project with fresh eyes.

You can arrange this in very different environments – as long as you have space where you can get someone to play, you are good. This could be at a B2C expo, on the show floor, where you have taken a booth specifically for that purpose; it can be in the exhibitors area of a B2B event; or it can even on your laptop, in the corridors of a conference where you persuade friends of friends to give your baby a spin.

There is value in getting your game into the wild, but I think it also comes with some caveats, and this is from talking to many developers but also UX specialists, about the benefits of such endeavours:

- Don’t fool yourself into thinking that it can be the equivalent of a focus group. Players at an event are not experiencing your game in a good environment to provide structured feedback. They have their friends looking over their shoulder, they know the parents of the baby, so to speak, are looking at their every move, the environment is loud, maybe hot, with many distractions. They are not very likely to tell you your baby is ugly after playing for 10 minutes – they will see the eagerness in your eyes and they will tell you, “Absolutely, I had a blast, good job mate!”

- Games are not equal in how they are fit for being played at an event. Your couch multiplayer battle game with short sessions will garner a lot more interest than a turn-based 4X game. When planning to attend an event, if you want to put your game in the hands of others, think about how long you want them to play for, and what you want them to take away from playing the game. There could be a whole blog post on how to structure a game demo for an event, just think it through.

I think it is important for you to decide what you want to take away from the exercise. There are various options I can think of:

- Get a sense of the appeal of the game. So, it won’t be a focus group testing, but you can see if people are playing through the whole demo or not, and if they come back to try again. They might be drawn in by the visuals, or maybe they pass by your booth without a second look at it. Are other people intrigued by what is happening on the screen when someone is already playing?

- Recruit players. You want to get potential buyers of the game to learn about it and create interest for them. That’s a valid outcome to want from getting event attendees to play your game, but make sure you present a strong call to action to maximize the opportunity. If they play the game and then leave, how will they know the game is out months later? Give them flyers (not a big fan personally, even of the ones that are business cards size, they tend to end up in the nearest bin), get them to register to a mailing list (have a laptop at your station/booth, dedicated to this) or to follow you on your social networks. If you can think of a nice way to reward them for tagging you on Twitter, do it. If they enjoyed the game, they will want to make sure they can keep track of it – so give them the tools to do so.

While discussing this blog post with developers, one studio mentioned that to have the public play their game was an important part of their creative process. Being a small team, with no publisher, they found this was the best way for them to motivate themselves to meet milestones, and ensure the game was progressing constantly, with hard deadlines they had to meet.

This was very interesting, something I had not considered, and an excellent example of understanding the true motivation for you attending an event, and how you attend it.

Meet Your Community

Events represent an opportunity for you to meet your players. And I am not talking about your prospective players, the ones that might one day join your community, but actual, engaged fans that love what you do.

Connecting with those players in the flesh can be very interesting for developers. You can put a face to a name on forums, and they learn about the actual humans being behind the game. It is an opportunity to understand more directly what they are like, and what they like about your game. Not all games lend themselves to a highly engaged community over time, though, and it is not a goal that you will necessarily have for your own project. Moreover, meeting the creative team is usually more of an excuse for them to meet together than the actual end game. Creating a catalyst for your community to meet together and exchange is a positive aspect of this as well. It can be pretty casual, and you can meet them through a booth on the public showfloor you have at an event, or you can leverage the fact the event is happening to put together a dedicated, after-hours meet-up to make more out of your players gathering in the same place.

Evaluating the value of such endeavours is also complicated, but if you are unsure you can limit this to when other goals justify your attendance, and that way you can organise a meet-up for relatively low costs.

Events that are suitable for meeting your community will be ones that are open to consumers (for obvious reasons), and events that have a strong synergy or theme related to your own product. If your game is competitive, esports events are good for a meet-up, for instance.

Sell

While this is rarely the main goal, this is also something that is often forgotten or ignored as an option when considering the attendance of an event. Of course, there are events that actually prohibit you from selling anything on your booth, or force you to sell your product through dedicated shops (which might be perfectly fine options). Historically, video games events have been focused on games that are not yet available, making the selling of them a non-starter. However, it is now not so rare to see games exhibited at events after they have been launched, when they are readily available on various digital stores. Printing and selling Steam keys is not incredibly complex (make sure you do the proper accounting for them), and if visitors really enjoy your game, and they have the opportunity to purchase it there and then, they will. This is the strongest call to action you can have for a game. I worked the booth for a game a few years ago where we sold Steam keys, and we made enough money just from those sales to cover the cost of the booth and our travel expenses. It was a nice feeling to see at the end of the show that at the very least we had broken even, and we had also fulfilled all sorts of other objectives along the way.

If you happen to have t-shirts, badges, or other merchandise, they can nicely complement your games sales, or even serve as a valuable and profitable substitute, for them if the game itself is not available for sale.

It does take some extra effort, but even considering games sales, or related merchandising, is already more than what most companies I talk to usually manage.

Public events are the obvious fit for this (if you are selling B2B solutions, I would have to rethink the way I am presenting this blog post). Check whether the organisers allow selling at all, and if there are any event-specific restrictions or fees to acknowledge; what kind of audience is expected, and whether or not they would be likely to enjoy your game enough to buy it straight away, on site.

Celebrate

Having fun. It might be celebrating a milestone of your project, or even its release. Or it might be celebrating the joy of making games. Basically, the idea is that you are attending the event to have fun with your peers, maybe taking time off, away from the coal mine, to enjoy a bit of fresh air away from what you are toiling on.

I think it is important to recognize this motivation for what it is, and be very honest when it is driving your decision to attend. I think it is very easy to hide behind the other goals listed here, but it might not do you any good if you don’t recognize the true reason driving your decision. Otherwise, how can you make sure you accomplish what you had set your mind to? Here: did you have fun? Was the fun you had worth the time and expenses?

Not all events will offer the same type of opportunities, and how these opportunities are taken advantage of will vastly differ from one person to another. What matters is to understand what you are looking for, and whether or not the event is suitable for it. If you like late-night parties, with alcohol, then larger events, where companies are trying to woo the rest of the industry into liking them, are more likely to have multitude of such soirees. If your idea of celebrating is meeting players and the community, then check events with a good set-up for managing those kind of logistics. If you enjoy more quiet get togethers, where you can easily talk with other attendees, maybe look into what kind of official afterdark plans are organised at the event (that don’t involve a DJ, not enough seats for attendee bottoms, and copious free shots)

Building Brand Awareness

This is more likely to resonate with larger projects, the ones that you would consider the highlights of public events. As your marketing budget expands, attending an event in order to push the image that the project matters, and the world should pay attention to it, becomes a bigger priority. I think a project that illustrates this nicely is World of Tanks. While massively successful in its early days, it was often discarded as a Russian exception at best, and a mafia-money-laundering-front at worst. Once Wargaming put together a strategy to have the game present at all public events, usually with a massive booth and a real tank parked nearby, the perception shifted. It is one thing to hear about a game’s success on a website, but quite another to witness, in the flesh, hundreds of fans squeezed into a gigantic booth.

Brand awareness is also one of the motivations for most of the large booths at gamescom, whether you think of Farming Simulator or PlayStation. I guess it could be expanded to a general marketing goal, but really, I believe awareness is at the core here.

With this type of focus in mind, the one criteria for attendance at an event is going to be the scale of the event (how many people will attend) and how much of that audience you haven’t reached yet (for instance, it doesn’t matter if an event is smaller if it happens to be in a country where you haven’t showed the game yet). Of course, this is mostly considered for B2C events, with exceptions like E3 coming to mind. Media appeal should also be part of your consideration, as a strong media attendance can significantly multiply the visibility of your project.

Market Intelligence

Last in my list, and if you do have other goals let me know, is getting a sense of the industry trends. I guess all events will offer a window onto those in some ways, but I would say, to get a prospective look at them, conferences are usually the best. While there is content that is about looking backwards, a lot of the program managers try to get ahead of the trends and invite lecturers with an eye on what’s on the horizon. You will still learn a lot from walking the halls of a professional convention, though – there will be games you had not heard of, or that you forgot about. Also, there will be creative ways to present a game you had not thought about, and genres you didn’t know were popular, with hordes of fans queueing to get their hands on some of its swag.

It should be relatively easy for you to estimate if you met that goal after an event. Do you feel you have a better sense of the trends? Can you list them? Were you surprised by any of them? If you can answer those questions, you are in a good place to understand whether or not it was worth attending, when it comes to this motivation.

Description

The idea is for the id cards to be as easy to read as possible. I want the description to be as short and to the point as possible, and mostly just have it provide some context for the event.

I will try to avoid to editorialize them too much, but each will be based on my inevitably, and naturally biased understanding of the event.

Costs

When I was discussing the idea of the id cards with peers, the information about the cost to attend came up very frequently. But do bear in mind that such figures can be difficult to estimate and subsequently communicate properly. The cost list will always be illustrative of the bare minimum to attend or exhibit at the event itself, representing a ballpark figure to help compare different events with each other.

Equally, you can benefit from an event without attending its main component, and save a significant amount of money.

And as I mentioned earlier, I won’t take into account travel and other expenses, such as hotel and food. There are just too many variations, and you should be able to run your own estimates for these.

On Reducing Costs

There are many ways to reduce the costs of your attendance, and I thought I would mention a few here, even though this could be a topic in itself:

- Be a speaker. That will only work for conferences, but many events have a conference component. Be aware, however, that it is uncommon for the organizers to cover more than the ticket to attend, and it is even rarer to be paid to be a speaker.

- Work with a “booth aggregator”. Is there another word for the likes of the Indie Megabooth or the Indie Arena? Anyhow. These folks. Working with them to be an exhibitor might not always save you money directly, but it will save you a lot of hassle and lot of energy ahead of the event, and that equates to time you can spend on other things, and is as good as money.

- Keep an eye on the free opportunities. Some events save space to invite projects that are different from their regular, mainline programming, or that don’t have the budget to normally attend. Jump on those opportunities. A good example is the Leftfield Selection at EGX.

- Talk to your local trade body. Many of them arrange combined booths, or export missions, and they can be subsidized partly or in their entirety. ICO’s presence at gamescom every year is made so much better because we do it with UKIE.

- Double check you are not entitled to some discounts. Students often receive discounts for conference tickets, having an IGDA membership can lead to some discounts at game events, and discounted Early Bird pricing is the norm for a lot of events.

The first set of cards

And to conclude, please find my first set event of events cards. They are all hosted on Imgur, you can save the url of the album for future reference, and I will tweet new cards on my account as well as ICO Partners’ as I make them.

If there is a specific event for which you would like a card made, let me know. This is just the beginning, and I plan on adding to this regularly.

Where to find more events?

I use two websites to keep track of industry events:

- Game Confs. Very simple list of events, with filters per country or per continent.

- Events for Gamers. A bigger website, with many events listed. They also have a Google calendar. It’s just one click to add it.

Many of these lists are difficult to maintain, so don’t rely solely on them. My next best source for industry events is Twitter, which I keep an eye on for events announcements.